Self-Regulation Skills and the Link with Social-Emotional Wellbeing

What the research says…

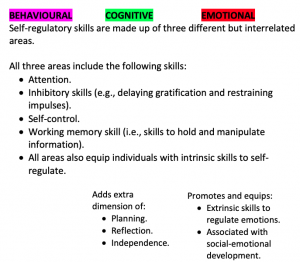

The importance of social-emotional development has been clearly established, especially in recent research with the emphasis on social-emotional health and wellbeing (6,11,12). There is now also an awareness of the link between social-emotional development and self-regulation skills. Thus, there has been an increase in research in this area, including a focus on the effects of these two areas of development on school readiness and early academic achievement (2,3,12,15).

As a result of these findings, it has been acknowledged that early development and support of these regulatory processes, or commonly referred to as self-regulation skills (including the development of behavioural, cognitive/executive functioning and emotional self-regulation skills) are of great importance.

However, it has only been in the last ten years that research has really focused on the importance of the development of self-regulation and importantly in interaction with those beyond the family context, in particular within early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings, compared to a primary school settings (as most past research have concentrated on). Examples of primary school studies included those cited by Mortensen et al. (2015), (including, Mashburn et al., 2010; Rudasill et al., 2009; Sabol et al., 2012), as well as other studies cited by Rudasill et al. (2016), (such as Hamre et al., 2001; O’ Connor, 2010; Rudasill, 2011).

THE PRESCHOOL YEARS

There are three main types of factors within the ECEC context that have been found to positively and effectively influence the development of regulatory processes in the preschool years, protective factors that ECEC contexts can easily tailor into their classroom. These protective factors have been found to have correlated benefits to all children – children from positive and less positive backgrounds – that is, children having experienced more at-risk contextual factors.

THE THREE MAIN TYPES OF FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGULATORY PROCESSES

* PROTECTIVE FACTOR 1

TEACHER QUALITY >>> CHILD-CENTRED BELIEFS

The first main factor that was identified to be influential in an ECEC context was teacher quality, but what this actually included was somewhat unclear and undefined. So to clearly understand what teacher quality actually was required further analysis of studies.

The following child-centred beliefs = factors of teacher quality:

- Making curriculum and classroom decision, including having authoritative leadership and organisational structure, whilst promoting autonomy among children. As well as teaching through sensitive interactions and caring relationships (10).

- This correlated to growing self-regualtion, namely behavioural self-regulation (10).

CURRICULUM DECISIONS

Though academic outcomes could not directly be linked to child-centred beliefs and practices, there was an indirect relationship between those practices. This was a result of increased self-regulatory processes, and as such, this furthered skills in literacy and maths (10).

- Rather than use more internal skills, which they would use when they got more skillful, it was proposed that through sociodramatic play children would be able to learn to externally regulate their emotions through scaffolded experiences with a more experienced teacher or peer to model and facilitate emotional self-regulation (18).

Additionally, through sociodramatic play…

- Behaviour would itself be regulated by the ‘role’ they adopted, while also being regulated by others.

- Within this safe ‘pretend’ world of scenarios there were no serious consequences to making the incorrect response. There were instead given opportunities to try again with the same or different strategies till they got it correct, and in doing so, refine their range of self-regulatory skills.

Curriculum decisions, another area of teacher quality.

Inclusion of active play was another important curriculum decision that had an influential effect. In the study by Becker et al. (2014) they had participants from Head Start preschools (who were preschool groups characterised as high-risk including children who have disabilities and physical delays, and who catered for children from low income families). Though this was a small sample, findings from the study were important in regards to the participants of the study and purpose.

- Becker et al. (2014) found that the inclusion of active play in the everyday curriculum improved the self-regulatory skills of children, particularly children who came from a high-risk background, as described above.

- They also found that there was a link between more active play and better self-regulation, in that children also showed higher literacy and maths skills, which was an indirect effect of using their self-regulatory processing skills obtained through the medium of active play.

It was significant to note the importance of curriculum decisions for individual needs, particularly for those who were more likely to have disabilities and physical delays. It was also important to know what factors were more likely to help and improve their skills.

CLASSROOM DECISIONS

Children’s most basic human LEARNING needs

- Include collaborative learning, giving the child autonomy, and promoting a sense of belonging and competence.

- Another area of child-centred practices and beliefs.

These concepts are all related to the issue of learning that takes place IN INTERACTION with others and the learning context (7,18).

When this type of learning was promoted, children’s basic human LEARNING needs were met, which meant lowered stress levels and less need to use emotion regulation. Overall, resulting in increased self-regulatory skills (7).

Learning that takes place IN INTERACTION with others and the learning context… meets children’s basic human LEARNING needs… resulting in increased self-regulatory skills

* PROTECTIVE FACTOR 2

A second major factor that was identified to be influential in an ECEC context was engagement. Engagement with teachers, in the classroom, as well as in class tasks. However, a key factor that was important to consider alongside this issue was classroom climate/environment.

ENGAGEMENT

The study by Williford et al. (2013b) found that children who were more engaged in class tasks were more positively engaged with teachers and this was correlated to an increase in task orientation.

- They also found that despite children being engaged in more negativity in the classroom, controlled emotional regulatory processing behaviours were related to positive engagement with teachers.

Another study by Williford et al. (2013a) added that in correlation with higher engagement in the classroom and with class tasks, this was related to greater gains in self-regulation.

- There was also a relationship between the quality of teacher interactions in the classroom and inhibitory control, along with an increase in receptive vocabulary.

- As a whole, these findings were related to better school readiness skills.

An environment is characterised by the relationships formed between teachers and children, which then influences children’s engagement in the classroom (3).

But how are these relationships supported? How is engagement heightened?

Through establishing the right….

CLASSROOM CLIMATE

Related to this second factor of engagement is the key factor of classroom climate/environment in relation to how emotionally and organisationally supportive the environment is.

In a study undertaken by Cadima et al. (2016) with a population of socially disadvantaged children, it was found that closer teacher-child relationships had a correlation with higher self-regulation.

- A finding was that it was not just closer individualised teacher-child relationships that helped self-regulation. It was ALSO necessary to consider the quality of support provided by the classroom environment – that is, the climate of the learning environment.

The study by Choi et al (2016) found similar findings when they looked at cognitive regulation/executive function (i.e., skills including planning, reflection and independence), specifically focusing on inhibitory control (i.e., skills such as delaying gratification and restraining impulses).

- The population of this study was based on children who were characterised by behaviour and emotion that were more negative, in particular, having lower/poorer inhibitory control.

- They found that children who came with lower/poorer inhibitory control benefited from emotionally supportive and well-organised classrooms.

- Interestingly, children from this group also made greater gains and improvement in inhibitory control than children who began and were on a normal trajectory of regulatory processes development.

- Therefore, initial child inhibitory control was not a factor in determining their trajectory.

- The key was teacher support, which enabled negative trajectories to be overturned and instead lead children to improved inhibitory control.

Inhibitory control and cognitive regulation were determined by both teacher-child interactions AND environmental climate established within the classroom (4).

- They found that emotional support assisted with low effortful control.

- While the reverse was found too. That is, negative emotional support limited and made inhibitory control (i.e., skills such as delaying gratification and restraining impulses) worse, which also increased teacher-child conflict.

Basing discussion around teaching practices and teacher-child interactions as well as how children are the active recipients of teacher interactions, there were further findings regarding emotional support of children with and without behavioural problems and teacher-child conflict (13).

- This suggested that children are ‘active’ in their own ecological context as a ‘child’/individual. In the same way teachers are ‘active’ in their ecological context as professionals in the ‘ECEC setting’ .

- When considering the mesosystem – that is, the interconnection between the different contexts, this meant that within the ECEC context children and teachers had bi-directional effects on one another. Specfically in relation to this discussion, when positive emotional support was provided negative class behaviour decreased, which included teacher-child conflict.

* PROTECTIVE FACTOR 3

The third and last main influential factor in an ECEC context was teacher-child relationships. The following studies build on the research by Cadima et al. (2016) and Rudasill et al. (2016), which were specifically related to the second protective factor.

- How children’s self-regulation related to social-emotional competence.

- How engagement in class and being emotionally supported by teachers related back to high-quality teachers and high-quality child relationships with others.

- The various studies in this area also found correlations to academic outcomes, namely literacy and maths outcomes.

In other studies, it was found that higher teacher-child relationships were correlated with higher self-regulation, as well as with higher maths skills in both preschool and kindergarten.

- This was because the skills that enabled children to excel in understanding and solving maths problems (i.e., skills related to the learning of maths) such as working memory, inhibitory skills, and cognitive flexibility were the same skills associated with developing behavioural and cognitive self-regulation (2).

On another academic level, there were significant findings in relation to the impact of teacher-child relationships and behaviour regulation on the effects of language development, specifically grammar skills.

In this study, they found that despite having high teacher-child conflict, a child’s grammar skills still increased (15). However, it was their level of behavioural regulatory skills that related to the amount of grammar gained.

- That is, more controlled behaviour regulation correlated with higher grammar skills.

- While lower behaviour regulation correlated with lower grammar gain.

- On the other hand, children with a weak (versus low) behaviour regulation had further risk for delay in language development. This was because teacher-child relationships that were characterised as having high-conflict, compounded experiences for children that impacted more areas of language development in addition to their grammar skills.

An additional study by Graziano et al. (2015) followed a group of children with externalising behavioural problems who were reported to have more difficulties with school readiness skills at preschool and difficulties when beginning school.

- They concluded from their findings that that the defining factor was the quality of relationships – the positive and closer teacher-child relationships.

- This correlated with executive function/cognitive regulation skills, teacher-rated school readiness and later school achievement.

THE DEFINING FACTORS…

THE DEFINING FACTORS…

- Skills that assist in school readiness and academic achievement such as, working memory, planning, and independence are the same skills required to develop self-regulatory processes.

- More importantly, Graziano et al. (2015) concluded that it was the quality of teacher-child relationships that could act as a protective factor for negative effects of self-regulatory processes.

It is important to note that the various types of factors from the ECEC setting...

- Did NOT actually raise self-regulation as a whole for children with ‘normally’ developing self-regulatory development or children who had well developed self-regulation skills.

- Instead, the three identified protective factors assisted in the development of self-regulatory skills and later school achievement. That is, the ECEC setting was another important ecological context in the life of children who were at-risk of developing low self-regulation. Not being born ‘at-risk’; but instead because of the interactive factors in their ecological context this affected the trajectory of their development in a less positive way.

As such, there are particular factors that act as protective, influential factors in the ECEC context that can support children to catch-up to their peers. In doing so, when provided with these more positive and effective factors in an ECEC context, children who were at-risk could make even greater gains, overtaking the skills and abilities of their peers who were on a ‘normal’, stable trajectory of self-regulatory development.

REFLECTING ON THE 3 PROTECTIVE FACTORS

The study by Gunzenhauser et al (2015)(9) looked at families from lower versus higher socio-economic status (SES), and discussed some important findings in regards to a mix of the three factors that influence behaviour regulation.

-

-

- Just because children were from higher-SES families did not mean they expanded the growth of their self-regulation or even that they had higher self-regulation.

- The opposite was also true for children from lower-SES families. That is, just because children were from lower-SES families did not mean they lowered their self-regulation or had lower self-regulation.

- Children from lower-SES families could still develop self-regulation to the same quality and even high self-regulation, as a positive contributing factor was the ECEC context.

-

CURRICULUM DECISIONS – More books vs. less books (9)

(Books – a measurement of home educational resources).

Despite being from a lower-SES, children with more books at home related to the support of the development of positive behaviour regulation.

However, some children from lower-SES had less books at home. In these cases the ECEC context became a protective factor by the curriculum decisions that were made. In particular, making books available and reading to children a focal part of the program.

-

- This would support the development of children’s varying levels of regulatory processing skills who were also from varying SES backgrounds.

TEACHER-CHILD RELATIONSHIPS – Is gender a risk factor… in the development of self-regulatory processing skills?(9)

Gender was found not to be a risk factor.

In fact boys who had low processing skills or at-risk of developing low self-regulatory skills when growing up in the context of an at-risk familial environment, actually had a higher rate bouncing back and ‘catching up’ compared to girls.

The key was teacher-child relationships characterised by verbally stimulating non-gender specific socialisation (9).

- The quality in relationships children developed with their teachers in the ECEC setting became a protective factor for children. A relationship that they may not have established or will develop in the home environment.

- Even more, when children developed these relationships characterised by this style of verbal socialisation this was found to have a significant impact on the development of children’s self-regulatory processing skills, particularly boys from lower-SES backgrounds(9).

**** REFLECT ****

Are you gender-specific in your verbal socialisation?

Eg: Being more emotionally supportive and verbally stimulating to girls vs. more physically playful with boys.

Empirical studies says that most families are not very aware. However, teachers in ECEC contexts are more aware of their interactions, and provide equal time and verbal stimulation to both boys and girls (Matthew et al., 2014; as cited in Gunzenhauser et al., 2015).

REFERENCES

(1) Becker, D.R., McClelland, M.M., Loprinzi P., & Trost, S.G. (2014). Physical activity, self-regulation, and early academic achievement in preschool children. Early Education & Development, 25, 56-70. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2013.780505

(2) Blair, C., & McKinnon, R.D. (2016). Moderating effects of executive functions and the teacher-child relationship on the development of mathematics ability in kindergarten. Learning and Instruction, 41, 85-93. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.10.001

(3) Cadima, J., Verschueren, K., Leal, T., & Guedes, C. (2016). Classroom interactions, dyadic teacher-child relationships, and self-regulation in socially disadvantaged young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 7-17. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0060-5

(4) Choi, J.Y., Castle, S., Williamson, A.C., Young, E., Worley, L., Long, M., & Horm, D.M. (2016). Teacher-child interactions and the development of executive function in preschool-age children attending Head Start. Early Education & Development, 27(6), 751-769. doi:10.1080/10409289.2016.1129864

(5) Degol, J.L., & Bachman, H.J. (2015). Preschool teachers’ classroom behavioural socialisation practices and low-income children’s self-regulation skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 89-100. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresjq.2015.01.002

(6) Denham, S.A., Bassett, H.H., Way, E., Mincic, M., Zinsser, K., & Graling, K. (2012). Preschoolers’ emotion knowledge: Self-regulatory foundations, and predictions of early school success. Cognition & Emotion, 26(4), 667-679. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.602049

(7) Fried, L. (2011). Teaching teachers about emotion regulation in the classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 117-127.

(8) Graziano, P.A., Garb, L.R., Ros, R., Hart, K., & Garcia, A. (2015). Executive functioning and school readiness among pre-schoolers with externalising problems: The moderating role of the student-teacher relationship. Early Education & Development, 27(5), 573-589. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2016.1102019

(9) Gunzenhauser, C., & Von Suchodoletz, A. (2015). Boys might catch up, family influences continue: Influences on behavioural self-regulation in children from an affluent region in Germany before school entry. Early Education & Development, 26, 645-662. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2015.1012188

(10) Hur, E., Buettner, C., & Jeon, L. (2015). The association between teachers’ child- centred beliefs and children’s academic achievement: The indirect effect of children’s behavioural self-regulation. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(2), 309-325. doi: 10.1007/s10566-014-9283-9

(11) Kragh-Muller, G., & Gloeckler, L.R. (2010). What did you learn in school today? The importance of socioemotional development – A comparison of U.S. and Danish child report. Childhood Education, 87(1), 53-61.

(12)Mortensen, J.A., & Barnett, M.A. (2015). Teacher-child interactions in infant/toddler child care and socioemotional development. Early Education & Development, 26(2), 209-229. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2015.985878

(13) Nurmi, J.-E., & Kiuru, N. (2015). Students’ evocative impact on teacher instruction and teacher–child relationships. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 39(5), 445-457. doi: 10.1177/0165025415592514

(14) Rudasill, K.M., Hawley, L., Molfese, V.J., Tu, X., Prokasky, A., & Sirota, K. (2016). Temperament and teacher-child conflict in preschool: The moderating roles of classroom instructional and emotional support. Early Education & Development, 27(7), 859-874. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2016.1156988

(15) Schmitt, M.B., Pentimonti, J.M., & Justice, L.M. (2012). Teacher-child relationships, behaviour regulation, and language gain among at-risk preschoolers. Journal of School Psychology, 50(5), 681-699. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.04.003

(16) Williford, A.P., Maier, M.F., Downer, J.T., Pianta, R.C., & Howes, C. (2013a). Understanding how children’s engagement and teachers’ interactions combine to predict school readiness. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(6), 299-309. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.05.002

(17) Williford, A., Vick Whitaker, J.E., Vitello, V., & Downer, J. (2013b). Children’s engagement within the preschool classroom and their development of self-regulation. Early Education & Development, 24(2), 162-187. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.628270

(18) Willis, E., & Dinehart, L.H. (2014). Contemplative practices in early childhood: Implications for self-regulation skills and school readiness. Early Child Development & Care, 184(4), 487-499. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2013.804069

© Tirzah Lim 2017